The Evolution of "Basic" D&D

It's a wild understatement to say that Dungeons & Dragons has gone through a lot of iterations, forms, and incarnations over the years. One of the first big schisms in the game came very early on, when the original version of the game evolved into Advanced Dungeons & Dragons.

I admit to being a bit fuzzy on the specific details of this evolution; it's possible that TSR originally intended to continue publishing OD&D alongside AD&D (otherwise, the need to clarify that the new game was "Advanced" seems superfluous), or it could simply have been a branding change. Regardless, around this time, they also decided that it might be a good idea to offer a "Basic" version of the game, to introduce new players.

Enter Eric Holmes, and the beginning of what would become the first "Edition Wars" in the history of the game. These edition wars continue even down to today's fans of the game, many of whom are starkly (and harshly) dismissive of the various versions of BD&D. Many players dismiss the various basic versions of the game as targeted at children, being juvenile or purile, or any number of other value-judgement-based insults.

I find these insults to be shortsighted and largely untrue, but that's really not the point of this blog. My good friend Tim Brannan over at The Other Side is working on a blog about just that issue, and I recommend you follow him if you're not already.

What I would like to do here is take a brief look at the actual, mechanical evolution of D&D as it applies to those basic games.

The original Holmes D&D is, essentially, a distillation of the core OD&D rules. By this time the Thief had come to be accepted as one of the "core four" classes (expanded from the original core three of Fighting Man, Cleric, and Magic User), so it appears. For the most part, Holmes maintains the essence of OD&D, importing few changes.

His rules only go up to level 3, and the reader is directed thereafter to pick up the AD&D books. In that sense it serves a similar function to the 5th Edition Starter Set. It still uses the term "Fighting Men," instead of "Fighter," and includes race as separate from class, as in OD&D. Classes were very limited--dwarves and halflings could only progress as fighting men, while elves progressed simultaneously as fighting men and magic users. There is an indication that other classes are available to these races in the AD&D books.

Perhaps the biggest change from OD&D in Holmes is the addition of the Good/Evil axis to alignment. This was possibly in response to an article Gygax previously wrote regarding the misunderstanding of what alignment represented, in The Strategic Review. There are essentially five alignments allowable in Holmes, rather than three: Lawful Good, Chaotic Good, Neutral, Lawful Evil, Chaotic Evil. Lawful and Chaotic Neutral didn't exist yet, nor did Neutral Good or Neutral Evil.

One interesting side-effect of Holmes is that in terms of this game, Fighting Men are rather weak in comparison to other character classes. Their ability to use any weapons and armor is their sole benefit, and it's not likely to make a huge difference against the cleric or elf (who gets that benefit and the ability to cast spells, though at the cost of slower advancement). The reason for this is that it uses OD&D's attack progression; that is, all classes have the same effective attack capability from levels 1-3.

This also becomes an issue when taking characters to AD&D, wherein fighters advance their attack capability every 2 levels. This is largely a symptom of Holmes' identity crisis--it is, on its face, a streamlined presentation of the first three levels of OD&D, but it points readers to AD&D to expand the game, when in truth it's only about 80% compatible with AD&D. Then again, I suppose back in the 70s, there was much more of a DIY aesthetic with the community than there is today. Today, gamers will be wailing and gnashing their teeth about "broken systems" with 80% compatibility. Back then, gamers mixed and matched systems and subsystems freely.

This game lasted for a number of years, and by all accounts was quite popular. Indeed, even today many gamers cite it as their favorite version of the game for its streamlined presentation, ease of plae, and wealth of options. A large number of resources and supplements were released, from monster matrices to monster and treasure cards, adventure modules and more. Today, one of the most popular retroclones in the OSR community is Labyrinth Lord, a very faithful re-creation of this rules set, which is available without art for free or in print or as a pdf with art from DTRPG.

I admit to being a bit fuzzy on the specific details of this evolution; it's possible that TSR originally intended to continue publishing OD&D alongside AD&D (otherwise, the need to clarify that the new game was "Advanced" seems superfluous), or it could simply have been a branding change. Regardless, around this time, they also decided that it might be a good idea to offer a "Basic" version of the game, to introduce new players.

Enter Eric Holmes, and the beginning of what would become the first "Edition Wars" in the history of the game. These edition wars continue even down to today's fans of the game, many of whom are starkly (and harshly) dismissive of the various versions of BD&D. Many players dismiss the various basic versions of the game as targeted at children, being juvenile or purile, or any number of other value-judgement-based insults.

I find these insults to be shortsighted and largely untrue, but that's really not the point of this blog. My good friend Tim Brannan over at The Other Side is working on a blog about just that issue, and I recommend you follow him if you're not already.

What I would like to do here is take a brief look at the actual, mechanical evolution of D&D as it applies to those basic games.

Terminology

First, let's clarify how I'm going to talk about these games. There are several versions of the "Basic" (including the expert, companion, etc., rules). The versions get very muddled as one gets into the 1990s, so I'm going to stick to the direct original evolutions, these being:

- The original version that comprised 3 little brown books in a woodgrain or white box, will be referred to as OD&D.

- The first Basic Rules version, written by Eric J. Holmes, will be referred to as Holmes.

- The next version, written by Tom Moldvay, David Cook, and Steve Marsh, will be referred to as B/X. This is the first version to have an "Expert" set.

- Third, the most well-known version of this branch, is that edited and revised by Frank Mentzer. This will be called BECMI, as it was the first set to take characters all the way to godhood.

- Closely associated with BECMI was a later "second edition" of this particular iteration, which saw it revised, re-edited, streamlined, and placed into a single hardcover book, the Rules Cyclopedia. For the most part I'll deal with that and BECMI together, but when referring to it specifically, I'll use the term RC.

- Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, of course, will be AD&D.

A Word About Brevity

Of necessity, this particular look at basic D&D will be rather brief and concise. I will certainly overlook or ignore many of the details. My goal here is just to provide an overview. I'm certainly not an expert in this branch of the game--I've always been more of an AD&D player. Hell, I'm not an expert in any edition of the game, just a fan who's been involved since around 1979. Still, I think it's fascinating enough to be worth a look.

In the Beginning...

In the beginning, there was only wargames. Then, inspiried by ongoing Diplomacy-style takes on these wargames by a man named David Wesley called Braunstein, an enterprising man named Dave Arneson started running the first dungeon crawls. He later partnered with Gary Gygax, a leader in the local wargaming scene, and the result was OD&D, the first true role playing game in history (or at least, the first published game that would go on to identify itself in that manner).

OD&D was a grand experiment. As such, its rules were wide open, very minimalist. The 3 booklets that made it up provided a skeleton, a framework under which one could run a game, and did a great deal of referencing to Chainmail, a well-known wargame that was popular at the time (and which had been co-authored by Gygax).

As time went on, OD&D generated five sourcebooks (including Swords & Spells, a largely diceless successor to Chainmail which, while branded as a D&D book, doesn't carry a "Supplement V" designation). These books expanded the game options and its complexity, and it became clear that a reorganization would be required at some point in time, if for no other reason than to address the volumes of questions and fan mail that kept flooding the TSR offices, and to clarify what D&D meant, so far as organized tournament and convention play was concerned.

The result would be 1978's Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. While the game would go on to be wildly popular, the rules presentation was certainly complex and the concern was that fans would see it as arcane or difficult to suss out, so it was decided that a sort of "introductory" version of the game was needed, to exist alongside AD&D, which could introduce players to the core concepts of play.

Holmes D&D

John Eric Holmes was a science fiction author and professor of neurology who took on this task. It's worth noting that Holmes D&D arrived on the scene in 1977, a year before AD&D, so it was certainly not a response to fan demands, but rather, seems to be in anticipation of the need for such a set. Some have dismissed Holmes as an "outsider" who didn't understand D&D. Nothing could be further from the truth--he had written a number of articles about the game that were well received, and had even produced D&D-related fiction. He wasn't chosen in a vacuum.The original Holmes D&D is, essentially, a distillation of the core OD&D rules. By this time the Thief had come to be accepted as one of the "core four" classes (expanded from the original core three of Fighting Man, Cleric, and Magic User), so it appears. For the most part, Holmes maintains the essence of OD&D, importing few changes.

His rules only go up to level 3, and the reader is directed thereafter to pick up the AD&D books. In that sense it serves a similar function to the 5th Edition Starter Set. It still uses the term "Fighting Men," instead of "Fighter," and includes race as separate from class, as in OD&D. Classes were very limited--dwarves and halflings could only progress as fighting men, while elves progressed simultaneously as fighting men and magic users. There is an indication that other classes are available to these races in the AD&D books.

Perhaps the biggest change from OD&D in Holmes is the addition of the Good/Evil axis to alignment. This was possibly in response to an article Gygax previously wrote regarding the misunderstanding of what alignment represented, in The Strategic Review. There are essentially five alignments allowable in Holmes, rather than three: Lawful Good, Chaotic Good, Neutral, Lawful Evil, Chaotic Evil. Lawful and Chaotic Neutral didn't exist yet, nor did Neutral Good or Neutral Evil.

One interesting side-effect of Holmes is that in terms of this game, Fighting Men are rather weak in comparison to other character classes. Their ability to use any weapons and armor is their sole benefit, and it's not likely to make a huge difference against the cleric or elf (who gets that benefit and the ability to cast spells, though at the cost of slower advancement). The reason for this is that it uses OD&D's attack progression; that is, all classes have the same effective attack capability from levels 1-3.

This also becomes an issue when taking characters to AD&D, wherein fighters advance their attack capability every 2 levels. This is largely a symptom of Holmes' identity crisis--it is, on its face, a streamlined presentation of the first three levels of OD&D, but it points readers to AD&D to expand the game, when in truth it's only about 80% compatible with AD&D. Then again, I suppose back in the 70s, there was much more of a DIY aesthetic with the community than there is today. Today, gamers will be wailing and gnashing their teeth about "broken systems" with 80% compatibility. Back then, gamers mixed and matched systems and subsystems freely.

B/X D&D

Following Holmes, in 1981, we saw a new version of Basic D&D hit the stands. This one was edited by Tom Moldvay (and later, David Cook and Stephen Marsh), and interestingly, there's little indication that these gentlemen even took Holmes into account when producing this version of the game. Where Holmes was an effort to re-present OD&D in a fairly faithful form, while at the same time introducing the reader to AD&D, the first book in what would become B/X had a different goal entirely.

This was an effort to present Basic D&D as its own game, separate from AD&D. Some have hand-waved and dismissed this effort as attempting to "kiddify" the game, or appeal to "pre-teens" and "teenie-boppers," but in truth, there was a large sect of gamers who had been fans of D&D in its original form, who didn't take to the aesthetic, organization, presentation, or complexities of AD&D. These wanted a return to the "purer" form of the game they'd played in the mid-70s, and Moldvay/Cook/Marsh were making an attempt to give it to them.

Though the rules certainly are streamlined and presented in a very clear, readable, and concise manner, there is no language, nor is there anything in the presentation, that suggests it's designed for pre-teens or even teens, any more than it is for adults.

If Advanced Dungeons & Dragons was an effort to evolve and expand the game, while better codifying the various extra systems in the supplements, B/X was in a very real way, OD&D Second Edition. Like Holmes, it covered only character levels 1-3, but unlike Holmes, it dropped the Good and Evil axis, going back to a simple Law-Neutrality-Chaos alignment system.

A number of "firsts" appear in B/X. The standardized ability score bonus progression first appears here, for all abilities except for Charisma. All other abilities see a progression of -3 to +3, with the extremes existing at scores of 3 and 18, respectively, and others progressing at 4-5, 6-8, 9-12, 13-15, and 16-17.

Rather than 3-for-1 prime attribute shifts in ability scores tied to specific abilities, players could now alter prime requisites on a 2-for-1 basis after rolling them, lowering any ability they liked, with the exception of Constitution and Charisma.

Rather than 3-for-1 prime attribute shifts in ability scores tied to specific abilities, players could now alter prime requisites on a 2-for-1 basis after rolling them, lowering any ability they liked, with the exception of Constitution and Charisma.

Next, this is the first time we truly see the race-as-class that Basic versions of D&D are known for. Instead of elves, dwarves, and halflings being limited in their options for character classes, they now become classes unto itself. No longer are you a 4th level dwarf fighting man. You are now a 4th level dwarf.

This brings up another "first," at least of sorts. This edition of D&D adopts the AD&D convention of re-naming the Fighting Man as the Fighter.

Interestingly, while nominally characters go only to 3rd level (and still share the same level 1-3 attack progression that weakens fighters), there is an attack progression "for higher level characters" listed on page B27, allowing one, ostensibly at least, to extrapolate the means to raise your character at least to 4th level, if not all the way to 6th (assuming an "every 3 levels" progression) and beyond. You'd have to make up increasing class abilities, of course, though even though spells only go up to second-level, you could simply allow casters to cast spells more often. Just a thought.

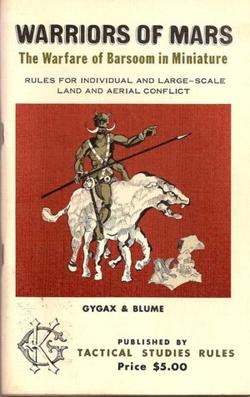

I saw one poster on social media express disdain specifically about monsters such as the White Ape, which has been divorced from Burroughs in this book. The poster insisted that it was, "like someone had no idea Burroughs even existed or what was going on in fantasy, like TSR never published Warriors of Mars."

In truth, TSR was sued over Warriors of Mars. The White Ape included here is a "serial numbers filed off" version. It pretty well mimicks the spirit of the one in Barsoom (though it only has 2 arms) but removes anything that could be construed as Burroughs, Inc., intellectual property. Personally I have no problem with this.

In line with this being the first version of the game to be a game unto itself that exists alongside AD&D, the Moldvay Basic rules were released alongside the D&D Expert Rules, the second volume of the B/X rules. This version, edited by David Cook and Steve Marsh, is why B/X is also often called the Moldvay/Cook/Marsh rules. This version allows you to take your characters all the way to 14th level, which honestly is years of campaigning in old-school terms, and is past name level, the point where most players retired their characters anyway.

It's worth noting that Holmes was never intended to exist as an unlimited play, long-term game, and no "Expert" set was ever planned for that particular iteration of the game. It was specifically designed to encourage OD&D players to try AD&D (regardless of Holmes' original intent, this was the drive of the edition by the time it hit the stands, as AD&D elements and references had been placed into it. Period.).

There are in the B/X rules tantalizing hints of a third, "companion" volume that would take characters to ultra-high levels (into the 30s) but sadly, these rules never materialized. It is of interest that in 2009, Jonathan Becker of Running Beagle Games released exactly such a volume, the B/X Companion, whilch assumes ownership of B/X and takes the game as it sits all the way to level 36, making use of all the hints offered in the original rules to extrapolate level progressions. It's well worth a read and I recommend it to fans of the B/X rules set. It doesn't seem that it's available in print anymore, though the PDF is sitll available through DriveThru RPG.

B/X, thus, is the first effort to present a new edition of the original D&D rules, a game that could exist alongside AD&D and appeal to both fans of the original game, and those who enjoyed the advanced version but wanted a new approach, new ideas, or even simplified systems to mix and match with their game (and indeed, many people ran Basic adventure modules with AD&D and never thought twice about the differences).

This game lasted for a number of years, and by all accounts was quite popular. Indeed, even today many gamers cite it as their favorite version of the game for its streamlined presentation, ease of plae, and wealth of options. A large number of resources and supplements were released, from monster matrices to monster and treasure cards, adventure modules and more. Today, one of the most popular retroclones in the OSR community is Labyrinth Lord, a very faithful re-creation of this rules set, which is available without art for free or in print or as a pdf with art from DTRPG.

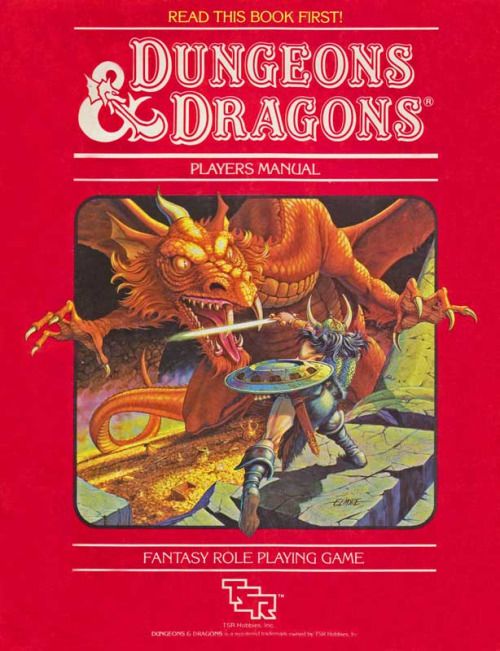

BECMI

Flash forward to 1983, two years later. The B/X rules had been quite popular with a range of support materials released. TSR decided that it was time for a cleanup and new revision of the rules, this one with a slicker presentation to match the success the company was enjoying. Enter Frank Mentzer, who revised the system from top to bottom and released what is now famously known as "red box D&D." This box featured a cover painting by Larry Elmore, and is probably the first game to take an approach of readability and ease of play from the outset.

Its box divided the rules into two booklets--a player's guide and a DM's guide. More than ever before, the player's guide section takes great pains to actually teach the game, including a solo adventure that would pre-figure the later TSR Endless Quest game books, which were Choose-Your-Own-Adventure style books that saw you playing a D&D character while making choices, complete with character sheet and hit points.

It's my feeling that this particular volume is the first time that D&D comes off as making a deliberate effort to be approachable to kids and teens; it's built to be fun to read and generate excitement and no longer uses language and arcane terms tied to older wargame communities. By this time in the early 80s, kids had grabbed onto RPGs in a big way, and there's no doubt that TSR saw young teens as an untapped market.

Of course, a major innovation with this set was that it was quickly followed not just by an Expert rules boxed set, but a Companion rules, Master set, and Immortals rules. Now, for the first time, players could take their characters from novice to god in the space of a campaign. Even AD&D didn't have concrete rules for achieving godhood. There were some "in passing" guidelines in Deities & Demigods, and the later Manual of the Planes, but nothing on the level of those in the Immortals box for BECMI. This was a major draw for a sizable portion of gamers.

Rules-wise, the changes from B/X are few; in terms of actual play it's about 98, 99% the same, and I had a hard time spotting concrete differences in terms of rules. The same universal -3 to +3 spread for ability bonuses was kept, now applied to Charisma as well (though the same oddly different Charisma reaction adjustment table from B/X is still carried over).

One interesting change is that made to demihumans. While they still were limited nominally in advancement, they were eventually given what I call "pseudo-levels"--that is, while they didn't call advancement "gaining levels" anymore after a certain point, they could improve things like spellcasting for elves and attack bonuses at certain XP benchmarks, effective, if not literal, level gain.

By and large, BECMI is a re-formatting and better organization of the B/X rules, designed to present a "step-by-step" how-to of playing D&D. If there's a difference, it's in terms of grit. It's a cleaner, sleeker, more accessible presentation that includes higher-level, more modern artwork by Elmore.

Indeed, so accessible was the BECMI rules that they lasted by and large all the way up until Wizards of the Coast bought TSR and released "D&D Third Edition," dropping the "Advanced" and ceasing support for the Basic game. There was a revision by Troy Denning in 1991 which made very few alterations, and was followed up by the Rules Cyclopedia in 1994.

The RC rules, again, were largely a cleanup and re-presentation of the BECMI rules. They did dump the Immortals set, favoring instead a streamlined, less evocative, and less workable set of immortal rules, which would later be followed by the Wrath of the Immortals boxed set. The loss of the Immortals rules, however, were the largest change. Unfortunately, the RC rules tend to be something of a mess in terms of presentation and organization that make them less accessible than the five boxed sets that came before.

There you have it--a brief history of the evolution of "Basic" D&D, from a standpoint of presentation and rules evolution. In the end, Basic D&D is really a continuation of OD&D in terms of presentation, concepts and play style, and it always surprises me that so many players and fans of the original woodgrain/white box OD&D rules are dismissive of it just because TSR attempted to make it accessible to more players.

Its box divided the rules into two booklets--a player's guide and a DM's guide. More than ever before, the player's guide section takes great pains to actually teach the game, including a solo adventure that would pre-figure the later TSR Endless Quest game books, which were Choose-Your-Own-Adventure style books that saw you playing a D&D character while making choices, complete with character sheet and hit points.

It's my feeling that this particular volume is the first time that D&D comes off as making a deliberate effort to be approachable to kids and teens; it's built to be fun to read and generate excitement and no longer uses language and arcane terms tied to older wargame communities. By this time in the early 80s, kids had grabbed onto RPGs in a big way, and there's no doubt that TSR saw young teens as an untapped market.

Of course, a major innovation with this set was that it was quickly followed not just by an Expert rules boxed set, but a Companion rules, Master set, and Immortals rules. Now, for the first time, players could take their characters from novice to god in the space of a campaign. Even AD&D didn't have concrete rules for achieving godhood. There were some "in passing" guidelines in Deities & Demigods, and the later Manual of the Planes, but nothing on the level of those in the Immortals box for BECMI. This was a major draw for a sizable portion of gamers.

Rules-wise, the changes from B/X are few; in terms of actual play it's about 98, 99% the same, and I had a hard time spotting concrete differences in terms of rules. The same universal -3 to +3 spread for ability bonuses was kept, now applied to Charisma as well (though the same oddly different Charisma reaction adjustment table from B/X is still carried over).

One interesting change is that made to demihumans. While they still were limited nominally in advancement, they were eventually given what I call "pseudo-levels"--that is, while they didn't call advancement "gaining levels" anymore after a certain point, they could improve things like spellcasting for elves and attack bonuses at certain XP benchmarks, effective, if not literal, level gain.

By and large, BECMI is a re-formatting and better organization of the B/X rules, designed to present a "step-by-step" how-to of playing D&D. If there's a difference, it's in terms of grit. It's a cleaner, sleeker, more accessible presentation that includes higher-level, more modern artwork by Elmore.

Indeed, so accessible was the BECMI rules that they lasted by and large all the way up until Wizards of the Coast bought TSR and released "D&D Third Edition," dropping the "Advanced" and ceasing support for the Basic game. There was a revision by Troy Denning in 1991 which made very few alterations, and was followed up by the Rules Cyclopedia in 1994.

The RC rules, again, were largely a cleanup and re-presentation of the BECMI rules. They did dump the Immortals set, favoring instead a streamlined, less evocative, and less workable set of immortal rules, which would later be followed by the Wrath of the Immortals boxed set. The loss of the Immortals rules, however, were the largest change. Unfortunately, the RC rules tend to be something of a mess in terms of presentation and organization that make them less accessible than the five boxed sets that came before.

There you have it--a brief history of the evolution of "Basic" D&D, from a standpoint of presentation and rules evolution. In the end, Basic D&D is really a continuation of OD&D in terms of presentation, concepts and play style, and it always surprises me that so many players and fans of the original woodgrain/white box OD&D rules are dismissive of it just because TSR attempted to make it accessible to more players.

This is excellent. I have a "companion" (heh) post to this coming up soon.

ReplyDeleteThanks for this wonderful retrospective on the rules!

ReplyDeleteYour article is very good, but the Rules Cyclopedia wasn't the end of the line. There were a couple of "Classic D&D" versions that were released as boxed sets that came out as well - the Black Box (large and small) versions that came out in 1991 at the same time as the RC, and the tan/gold Classic D&D boxed set that came out three years later.

ReplyDeleteThose two versions were little more than re-packaging. They flew largely under the radar regarding sales, and were intended specifically to guide users to the Rules Cyclopedia, much like Holmes was specifically intended to guide users to AD&D. In terms of system revisions, they offered next to nothing. So far as actual revisions and approaches to the game went, the Rules Cyclopedia was the endgame.

DeleteIn addition, as I said earlier in the article, "Of necessity, this particular look at basic D&D will be rather brief and concise. I will certainly overlook or ignore many of the details. My goal here is just to provide an overview." If I was going to be 100% thorough, I'd have to write an entire series on the Basic editions of the game. While that may happen some day, for now I just wanted to provide a broad look at the path the game took.

A very good, high-level, article! I've been searching for something like this for quite a while. The general "layout" of early edition D&D (I came in playing AD&D and never really understood what "Holmes" or "B/X" or "BECMI" referred to) has confused me for years. This is especially true of where the Rules Cyclopedia fits. Many thanks for clearing it all up.

ReplyDelete